Fasting triggers profound changes in the gut, brain and in food related behaviour.

With a bonus of protection against dietary carcinogens.

A new study from China has found that fasting can trigger dramatic changes in brain regions linked to appetite control and addictive behaviours, alongside measurable alterations in the gut microbiome.

Stool and blood analyses showed increases in several beneficial bacteria, most notably Coprococcus comes and Eubacterium hallii, further strengthening the growing body of evidence for a potent link between Intermittent Energy Restriction (“IER”, as described in the paper), fasting, gut health, and brain function.

As an additional benefit, the elevation of Eubacterium hallii (now more commonly referred to as Anaerobutyricum hallii), seems to offer some protection against xenobiotic heterocyclic amines (HCAs), which can be produced during the cooking of meat (muscle meat, as it contains creatine) due to the high-temperature pyrolysis of amino acids - and is a known risk factor for colorectal cancer.

Other foods, for ‘eggsample’ eggs, produce different heat-related compounds of concern, like advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), but I couldn’t find any evidence that this bacterium offers protection against them.

On average, participants in the study lost 7.6 kg (16.8 lbs) and showed measurable changes in both microbiota composition and brain activity.

In the brain, activity in the left inferior frontal orbital gyrus - an area responsible for regulating food intake - was reduced, suggesting that intermittent fasting fosters gut bacteria capable of producing compounds that influence brain activity in areas associated with appetite and impulse control.

This study shows, through functional MRI (fMRI) and metgenomic sequencing of stool samples that, even in a relatively short period of time - within a matter of weeks - not only are significant changes in gut bacteria and brain function observable, but food related behaviour is also affected.

We would see this as a subconscious change in eating patterns and food-related decisions. Fasting becomes easier, more effortless, and even desirable, like training a muscle, with the additional benefit of a more attentive brain. I can certainly attest to these profound physiological responses.

It’s a dynamic system, so the reverse is also likely true. - especially if you’re someone who is prone to grazing all day like a horse or cow.

Personally, I actually find that a complete fast is often easier than a day of caloric restriction, and I know I’m not alone in feeling that. Even with alternate day fasting, your body will habitually send signals to eat on your non-fasting days (usually at the same times of day) once you have adapted to the routine, while on fasted days you’ll stop feeling hungry.

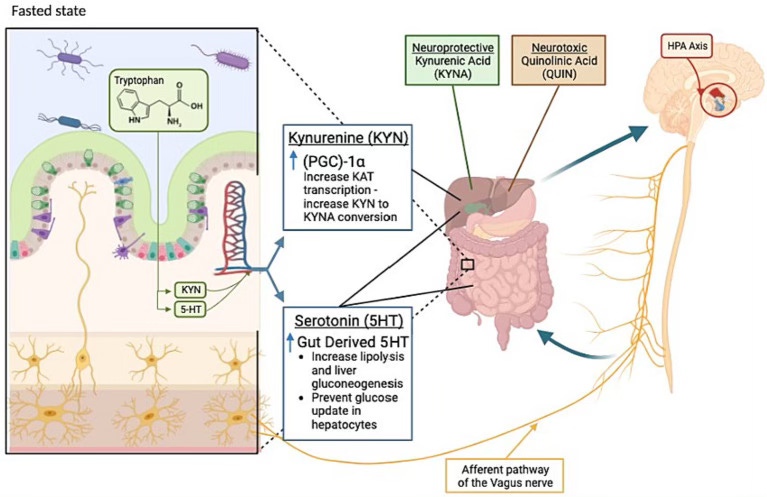

There is evidence for this adaptation, with primary mechanisms illustrated below. The graphic comes from a detailed narrative review of the impacts of “fasting diets” on human physiology, covering eating behaviour, sleep, mood and well-being.

What have we learned?

In a nutshell, the study from China indicates that there are clear, observable benefits beyond weight loss that are attainable in a relatively short period of time. It’s a dynamic system where butyrate-producing bacterium proliferate (as more harmful bacteria are eliminated) to improve insulin sensitivity, glycaemic control and food related behaviour in humans. These effects likely have a cross-over benefit to those with compulsions, addictions and mood disorders, which is what we see with diets that mimic a fasted state.

We already know that the type of intermittent fasting described in the study has been associated with improved metabolic health, sharper cognitive function, and longevity benefits. But, as technology continues to evolve, we’re finally able to dive deeper into the weeds, gaining an appreciation of how this relationship effects the brain, mind, gut and body as a whole.