Background:

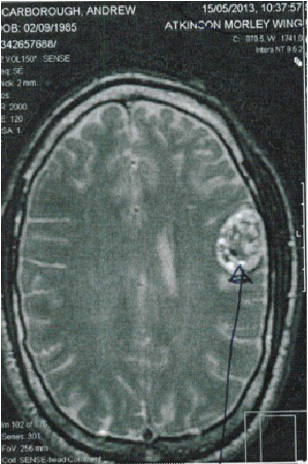

My initial diagnosis was unclear. I had just suffered a brain haemorrhage and the area of concern when viewed with a CT scan was suggestive of an arteriovenous malformation. It was explained to me that because the mass was so incredibly vascular and had essentially been like an erupting volcano in my brain, that at this point we could not have a clear idea of what we were looking at. Once my condition had stabilised (I was suffering from uncontrolled grand mal seizures), I had an MRI scan. The feeling at this point was that the imaging showed all the clinical features of a cavernous haemangioma, with a high degree of confidence.

Following surgery, I was informed that what was removed was in fact a high grade glioma brain tumour and that some disease remained in the motor cortex area of my brain. Histopathological investigations confirmed the diagnosis. Attempted removal of the residual disease could have had fatal consequences, so it was best to leave it. I had wondered if more would have been removed if I hadn’t been misdiagnosed. Perhaps I would have had an awake craniotomy, but I guess we will never know. It is possible that if that procedure was undertaken it may have resulted in noticeable deficits, so I don’t feel too sorrowful about that outcome.

What was the confusion surrounding my diagnosis and what does it mean?

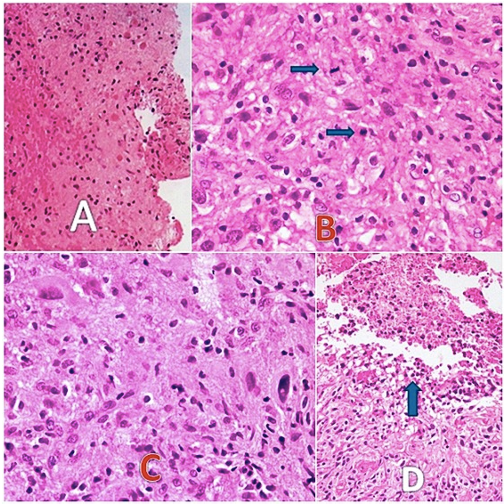

Interestingly, the tumour had all of the clinical features of a cavernous haemangioma along with those of an aggressive brain tumour. There was a cystic component, yet there was invasiveness and great proliferative potential.

A cavernous haemangioma can have a genetic cause if you have more than one, or they can just pop up out of nowhere and with no apparent reason. In my case it was the latter. A puzzle for me to work out. Nobody told me any specific information about any of this, I had to work it out for myself.

This ‘benign’ mass is known to cause seizures and in many cases if it isn’t genetic and lies in a ‘favourable’ location, individuals affected can live to a normal life expectancy. There has been debate over the years as to whether these entities can be classed as tumours or not. They are not made up of rapidly diving cells and do not spread to other parts of the body, so I’m still not sure what the basis of this discussion revolves around, notwithstanding the more recent cases of malignant transformation. I may need to investigate further.

In my own case, as is consistent with a few rare cases in the literature, it is possible that I had both a cavernous haemangioma and anaplastic astrocytoma brain tumour. Alternatively, and I believe most likely, is that the cavernoma had been there for many years and over time provided all the conditions for malignant transformation. This is fascinating to me and could potentially answer so many questions we have about brain tumours if we question the phenomena further, but nobody seems to care when I have mentioned it over the years.

Of course this situation remains extremely rare, however over time something likely provoked this reaction and I believe that could have been related to chronic stress I had been dealing with over many years, which finally came to a head with the migraines, bleed and subsequent brain haemorrhage. Recently I have been reading The Body Keeps the Score and The Myth of Normal exploring the evolving neuroscience of trauma, how we can understand it and recover.

My situation

My case is just my case. I should note that we put all these tumours into categories based on how they appear, molecular profiles and invasiveness potential, but every tumour is different and requires special consideration. Yes, there are commonalities, metabolically definitely, but you also get very unique tumour subtypes with very specific characteristics. Brain tumour classifications also change regularly and tumours can be re-classified, but that isn’t hugely important for this conversation as it would not have never been determined as being less aggressive.

I just realised that I have mentioned the words ‘cavernorma’ and cavernous haemangioma’, but haven’t really explained what it is properly. A cavernous haemangioma (aka ‘cavernoma’, cavernous angioma) is a cluster of abnormal blood vessels that doesn’t always cause symptoms, but can be deadly depending on where it is in the brain.

The range of symptoms can be quite broad and can be similar to those of a brain tumour. Interestingly, lower grade brain tumours are associated with a greater frequency of seizures because the neurones are more active, however in this case where we have a high grade brain tumour concurrent with a cavernoma, it becomes difficult to to make a clear assessment. IDH status and whether or not we are dealing with an oligodendroglioma brain tumour also has a bearing, but I won’t go into that.

In my situation, the haemocidirin that has been left over from the suspected cavernoma and haemorrhage I sustained can actually still trigger seizures if that area of my brain is overstimulated. I have added a link in text to explain why and how this occurs. I actually made a video of this 6 years ago of my own MRI, but I didn’t provide much context for some reason. I was still young and naive I guess.

When cavernomas are symptomatic they can result in instances of bleeding, seizures and headaches, as well as a host of neurological issues including dizziness, difficulty with speech, double vision, and problems with balance and tremors. As with brain tumours, some people may feel weak, numb, or excessively tired, and may also face challenges with memory and concentration. In severe cases, they might even lead to a specific type of stroke called a haemorrhagic stroke. I experienced all of these and they increased in intensity over time until I suffered a near fatal haemorrhage.

Symptoms are typically variable in their severity and duration, and much depends on the size, location and number of cavernomas. The situation can escalate if the cavernoma bleeds or exerts pressure on certain brain areas. The cavernoma's cells are typically thinner than those lining normal blood vessels, making them prone to leaking blood.

Theoretical causative factors of my brain tumour:

One possible and very likely explanation is that early on in my life there was some trigger causing an inflammatory response in that area of my brain. It could have been that the cavernoma had been sitting there asymptomatically from a young age and that over time it had undergone malignant transformation. This is a plausible explanation as I discovered similar cases in the literature, despite it being such a rare occurrence.

What could have triggered this?… (one or combination of theoretical factors to provide the conditions for the formation of this kind of tumour)

Prior brain injury - Setting up all the conditions for malignant transformation. Over recent years we have more studies supporting the idea that under rare circumstances and in individuals who are predisposed in some way, neuroinflammatory cascades triggered by an acquired brain injury have the potential of developing a tumour in this area. In February of this year, the case for this supposition was further strengthened with research from the UCL Cancer Institute. They reveal mechanisms of how brain injury may contribute to the development of glioma brain tumours.

Trauma and significant prolonged psychological stress - Throughout my childhood, from a young age I sustained significant trauma, depression, and disordered eating. It got pretty severe at one stage, but I won’t go into detail. There were some bright moments and I’m not treating myself at all like a victim as it’s all relative and everyone has a story, but it’s something to note.

Being born with jaundice and being in a special incubator. - I have no idea if this could have been a cause for anything, but I know that if this kind of jaundice goes untreated, it can cause a condition called kernicterus. Kernicterus is a type of brain damage that can result from high levels of bilirubin in the baby’s blood. I don’t currently have poor liver detoxification, but I have wondered if I may have had low level brain damage from hyperbilirubinaemia, which has been shown to result in a number of neurological issues.

Dental procedures - Growing up I had extensive orthodontic work. I don’t know what effect having a chunk of metal in your mouth for years has, especially for a growing child, but it wasn’t a pleasant experience in the 90’s and early 00’s. On top of that I had quite a few x rays and I remember having various scans following a pretty crazy car crash as a child that I still remember vividly.

Rare diseases - A routine visit to the dermatologist brought about some concern that I may have an extremely rare variant of a skin condition of Xeroderma Pigmentosum. This theory seemed ridiculous to me having investigated the condition. I tan easily and I love the sun.

Interestingly, the variant of concern is described as being atypical for the disease as a whole, which is normally seen as some kind of severe ‘sun allergy’ that can result in skin cancer. It is characterised by a unique type of freckling all over the body. The variant in question that my dermatologist was curious about had been shown to have no obvious consequences during development, and those affected can even tan with no apparent problems, yet in the second decade of life began to develop glioma brain tumours.

I had a skin biopsy and several investigations at Guys Hospital. I wrote about this in a short blog entry in 2015. It was a wild experience and every stage was pretty bizarre, yet fascinating. I also went through medical photography in a cold, dark room. All tests came back negative thankfully, but I learned a lot from the experience. I could write more about this if anybody is interested, it happened a few years ago.

Viruses - I lived in an area of Germany with a lot of tics and was bitten often. I never had a test for Lyme disease.

Vaccines (controversial and unknown) - I’m not going to go into this as it isn’t something I’ve looked into enough and it’s pretty controversial, but seems possible from the little amount I do know and of the adjuvant compounds that are in many vaccines.

Possible contributory factors:

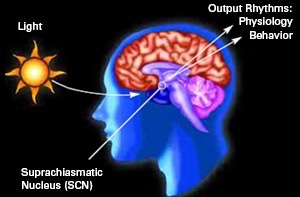

Circadian mismatch - Insomnia had been an issue for me over the years before my diagnosis and I spent too much time working long hours under artificial light. I also relied on caffeine for energy, since my brain tumour diagnosis I have avoided stimulants completely and I routinely get good quality sleep.

We know that every cell has clock genes and the SCN in the brain is the master circadian pacemaker. It makes sense that this kind of dysregulation, particularly over a sustained period of time (until it becomes unsustainable), could provide the conditions for malignancy in the brain. It remains controversial whether this circadian rhythm disruption is a cause or an effect of tumourigenesis, however it is highly likely in my opinion and mechanisms exist.

Seed oils - Too much omega 6 in the diet, particularly an abundance of linoleic acid could be problematic. Before my diagnosis I limited animal fats in my diet and I would cook with plant oils that don’t have a high smoke point. This is terrible.

There is an interesting discussion on seed oils and sugar here if you are interested. It is also interesting that in and around these brain tumours there is a pronounced different in fatty acid profile compared to normal brain tissue. Also, the migratory properties of malignant glioma cells have been shown to be modified by altering the ratio of AA:DHA in growth medium, with increased migration observed in AA-rich medium.

Hyperinsilenaemia - I followed a low fat, high carb pescatarian diet before my diagnosis and would get hungry every 2-3 hours. I would attempt to justify this by saying to myself I was so active that it was necessary and actually a good thing, but I would feel dizzy if I didn’t eat often.

I can now comfortably not eat for many days if I necessary, and interestingly my eating is not disordered in the way that it was before going on a ketogenic diet.

Final thoughts:

These are just a few ideas I’ve had in my mind over the years and doesn’t necessarily reflect what may have happened. It is of course possible, as I mentioned in part one, that there was some environmental exposure that caused a highly vascular brain tumour to develop. We have seen many cases (mostly in the US) of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) causing brain, lung and thyroid cancers in particular. Exposures could have either come from the air, water, ground or even some viruses.

In the past I have encountered mechanics and construction workers who have developed high grade glioma brain tumours and it never surprised me. People should really be more aware, especially when being exposed to vapour, fumes and even doing DIY in poorly ventilated environments (eg. painting with the windows closed). It amazes me that people are willing to wear a mask for a respiratory virus (where there is little evidence to support it), but will not consider any protective equipment when directly exposed to wet paint or fumes from roadworks. I learned that if this type of exposure smells like rotten eggs you should be particularly concerned, as this is the type of smell victims of cancer clusters have reportedly described.

It is possible that there may have even been a small cancer cluster in the area I lived, that I wasn’t aware of at the time. Who knows?! It’s difficult to tell because unless there is a major, obvious sign, nothing will be documented. I notice this happening much more in the US and I have often wondered whether communities who are impacted are just better at investigating these things and see it as more of a thing to look out for.

I hope you have found this article interesting. I could say a lot more, but chances are it wouldn’t read too well. If you have anything you would like to add, please let me know in the comment section.